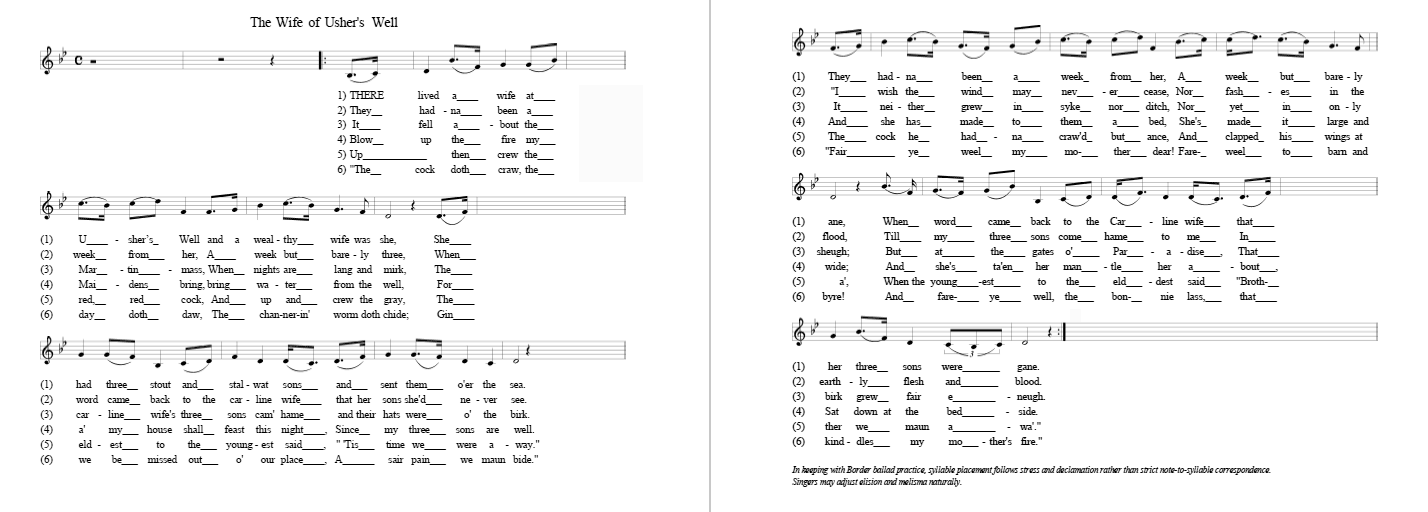

| 1) THERE lived a wife at Usher’s Well, And a wealthy wife was she; She had three stout and stalwart sons, And sent them o’er the sea. They hadna been a week from her, A week but barely ane, When word came back to the carline wife, That her three sons were gane. |

4) “Blow up the fire, my maidens! Bring water from the well! For a’ my house shall feast this night, Since my three sons are well.” And she has made to them a bed, She’s made it large and wide; And she’s ta’en her mantle her about, Sat down at the bedside. |

| 2) They hadna been a week from her, A week but barely three, When word came to the carline wife, That her sons she’d never see. I wish the wind may never cease, Nor fashes in the flood, Till my three sons come hame to me, In earthly flesh and blood!” |

5) Up then crew the red red cock, And up and crew the gray; The eldest to the youngest said, ” ‘Tis time we were away.” The cock he hadna craw’d but ance, And clapped his wings at a’, When the youngest to the eldest said , “Brother, we maun awa’. |

| 3) It fell about the Martinmas, When nights are lang and mirk, The carline wife’s three sons cam’ hame, And their hats were o’ the birk. It neither grew in syke nor ditch, Nor yet in ony sheugh ; But at the gates o’ Paradise, That birk grew fair eneugh. |

6) “The cock doth craw, the day doth daw, The channerin’ worm doth chide ; Gin we be missed out o’ our place, A sair pain we maun bide. “Fare ye weel, my mother dear! Fareweel to barn and byre! And fare ye weeL the bonnie lass, That kindles my mother’s fire.” |

Refresh to contract

| 1) THERE lived a wife at Usher’s Well, And a wealthy wife was she; She had three strong and sturdy sons, And sent them over the sea.They had not been a week away from her, A week, but barely one, When word came back to the old woman wife, That her three sons were gone. |

4) “Stir up the fire, my maidens! Bring water from the well! For all my house shall feast this night, Since my three sons are well.”And she has made a bed for them, She made it large and wide; And she has wrapped her mantle about her, And sat down by the bedside. |

| 2) They had not been a week away from her, A week, but barely three, When word came to the old woman wife, That her sons she would never see.“I wish the wind may never cease, Nor the waters rest in the flood, Until my three sons come home to me, In earthly flesh and blood!” |

5) Up then crowed the red, red cock, And up and crowed the gray; The eldest to the youngest said, “It is time that we were away.”The cock had not crowed but once, And flapped his wings at all, When the youngest to the eldest said, “Brother, we must go.” |

| 3) It happened about the time of Martinmas, When nights are long and dark, The old woman wife’s three sons came home, And their hats were made of birch.It neither grew in stream nor ditch, Nor yet in any trench; But at the gates of Paradise, That birch grew fair enough. |

6) “The cock does crow, the day does dawn, The murmuring worm complains; If we are missed from our appointed place, A bitter pain we must endure.Farewell to you, my mother dear! Farewell to barn and byre! And farewell to the pretty young lass Who kindles my mother’s fire.” |

This shortlink

https://1000-good-songs.org/p/597

Refresh to contract

The poem is in Scots, considered a distinct language closely related to English, or a continuum of dialects.

The text origin is traced to Child Ballad No. 79 in Francis James Child’s authoritative 19th-century collection of English and Scots ballads.

The earliest known printed version of the ballad dates to Sir Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802). Scott included the ballad in his influential anthology of traditional ballads from the Scottish Borders. Scott indicated the lyrics he printed were taken “from the recitation of an old woman residing near Kirkhill, in West Lothian” — plainly attributing the words to an oral source, not to himself as author.

Carline wife:

In “The Wife of Usher’s Well”, the Scots phrase “carline wife” means an old woman, with a harsh, ominous, or uncanny coloring rather than a neutral one.

-

carline / carlin / carline (Scots): an old woman, often implying crabbiness, witch-like qualities, or social marginality

-

wife (Scots): simply woman (not necessarily married)

“Carline wife” means,

an old woman, often with a grim, uncanny, or morally ambiguous connotation.

The phrase is not affectionate. It frames the mother as:

-

aged and hardened by grief

-

socially isolated

-

dangerously close to the supernatural

Her imprecation (calling her sons back) is what breaks the natural order. Labeling her a carline subtly aligns her with folk beliefs about women whose words carry power, for good or ill.

-

Not simply descriptive (age)

-

Not fully accusatory (she’s not called a witch outright)

-

Suggestive: she is a woman whose grief has tipped into something fearsome

“Carline wife” in the ballad signals an old, formidable woman, edged with folk suspicion and tragic severity—a figure whose sorrow is potent enough to summon the dead.

Fashes:

In Scots, “fashes” (from fash, fashe) means troubles, worries, vexations, or anxious cares—and in The Wife of Usher’s Well it carries a loaded emotional and theological weight, not just a casual “bother.”

Core meaning

-

fashes = griefs, cares, troubling anxieties

-

Stronger than “troubles,” closer to afflicting worries that gnaw at the heart

Why it matters in the ballad

When fashes appears in this ballad tradition, it signals:

-

Maternal anguish

-

The wife’s grief is not momentary; it is sustained, inward torment.

-

The word implies rumination—cares that will not let her rest.

-

-

Moral pressure

-

In Scots religious culture, fashes often connotes worldly cares that should be borne with submission.

-

Excessive fashes can shade into impatience with Providence.

-

-

Causal force

-

The mother’s fashes are not merely descriptive; they drive the narrative.

-

Her unceasing sorrow and ill-wishing disturb the natural order and precipitate the sons’ return.

-

Contrast with nearby terms

-

sair = pain felt

-

fashes = pain brooded over

-

maun = inevitability that follows

So fashes marks the interior engine of the tragedy.

In performance and underlay

Traditionally, fashes is:

-

stressed, not tossed off

-

often placed on a melodic peak or lengthened note

-

sung with a sense of heaviness rather than anger

Bottom line

“Fashes” in The Wife of Usher’s Well means more than “troubles”: it names a deep, brooding grief whose persistence upsets the moral and natural order and propels the tragedy forward.

Martinmas:

The feast day of Saint Martin of Tours, celebrated on 11 November; by coincidence, 11 November is the date of the Armistice that ended active fighting in the First World War, at the 11th hour.

Birk:

In Scots, birk fundamentally means birch (tree), but in poetry and ballads it carries several related connotations, and writers often play more than one sense at once.

Core meaning

-

birk = birch tree (Betula)

-

A very common Scots word, especially in older verse and song

Main connotations in Scots poetry

1. Literal birch tree / birchwood

This is the base sense.

-

Refers to actual trees, woods, or landscape

-

Birch is common in Scotland and visually distinctive

Example sense:

under the birk → under the birch tree

2. Youth, freshness, vitality

Because birch:

-

Leaf out early in spring

-

Have pale, “clean” bark

-

Are associated with renewal

birk often implies:

-

Youthfulness

-

Fresh growth

-

New life

This is especially common in love lyrics and seasonal verse.

3. Courtship / trysting place

In ballads and songs, birk frequently marks:

-

A meeting place

-

A liminal space between society and wilderness

So:

by the birk

often quietly signals romantic or secret encounter, even if nothing explicit is said.

4. The birch rod (discipline / correction)

Less common in lyric poetry, but present in Scots usage:

-

the birk = a birch switch

-

Used for corporal punishment (school, domestic discipline)

This sense introduces:

-

Authority

-

Hardness

-

Pain or correction

Poets sometimes exploit the tension between soft leafy birk and hard punishing birk.

5. Place-name and symbolic landscape marker

In older poetry, birk can function almost like a symbolic landmark:

-

A threshold

-

A boundary between life/death, home/wild, human/supernatural

This is especially relevant in ballads with uncanny or supernatural elements.

Are there multiple connotations in the poem?

Yes — very often deliberately so.

In a single poem or ballad, “birk” may simultaneously evoke:

-

A literal tree

-

Youth or life

-

A meeting place

-

Vulnerability (exposure)

-

Or, by contrast, the potential for hardness or correction

Poets relied on their audience’s familiarity with these layers. The word is economical but rich.

“Birk” in Scots means birch, but in poetry it commonly carries layered meanings: nature, youth, courtship, liminality, and sometimes discipline.

Whether more than one connotation is active depends on context—but in traditional verse, it often is.

Syke:

In Scots, “syke” (also syke, sike) primarily means a small stream, rill, or marshy ditch, but in poetry it carries strong symbolic weight.

Core meaning

-

syke = a small watercourse

(often a trickling stream, wet hollow, or drainage channel)

Connotations in Scots poetry and ballads

Depending on context, syke can suggest:

-

Liminal ground

A boundary space—neither dry land nor full river—often marking transition or unease. -

Melancholy / grief

Quiet, persistent water becomes a natural image for sorrow, tears, or enduring lament. -

Isolation or wildness

Sykes run through remote or uncultivated places, reinforcing solitude or abandonment. -

Life moving on

A small but continuous flow can imply time passing or life continuing despite loss.

Why poets choose syke

Compared with burn (stream) or river, syke is:

-

smaller

-

quieter

-

more intimate

That makes it ideal for subdued, tragic, or inward scenes.

“Syke” means a small stream, but in Scots verse it often evokes liminality, quiet grief, and the soft persistence of sorrow or time.

Sheugh:

In Scots, “sheugh” (pronounced roughly shugh or shooch) means a deep ditch, trench, ravine, or cut in the ground, and in poetry it carries strongly negative and ominous overtones.

Core meaning

-

sheugh = a deep furrow, ditch, gully, or trench

-

Often man-made (defensive ditch) or sharply eroded

-

Deeper and harsher than a syke

Connotations in Scots usage and poetry

Beyond the literal sense, sheugh commonly suggests:

-

Danger or obstruction

Something you can fall into, be trapped by, or be separated by. -

Boundary or division

A physical and symbolic line between states—safe/dangerous, living/dead, known/unknown. -

Death or burial imagery

Because a sheugh resembles a grave cut or trench, it often echoes mortality. -

Harshness and severity

Compared with gentler landscape terms, sheugh implies rough ground, hardship, and exposure.

Contrast with related Scots terms

-

syke → small, wet, melancholy stream (soft, liminal)

-

burn → normal stream (neutral)

-

sheugh → deep, dry or wet cut (hard, threatening)

Poets choose sheugh when they want severity, depth, or peril, not pastoral calm.

“Sheugh” means a deep ditch or trench, and in Scots verse it often signifies danger, division, and proximity to death or the grave.

Maun:

In Scots, “maun” (also mun, maun) means “must”, but with a strong sense of inevitability or compulsion.

Core meaning

-

maun = must, have to

Connotations and force

Compared with neutral must in modern English, maun often carries:

-

Necessity imposed from outside (fate, law, duty, circumstance)

-

Resignation rather than choice

-

A sense that resistance is futile

In ballads and poetry

In traditional Scots verse, maun frequently signals:

-

Fate or doom (“they maun gang”)

-

Moral or social obligation

-

Unavoidable loss or separation

It often heightens tragedy by emphasizing lack of agency.

“Maun” in Scots means “must,” but it strongly implies inevitability—something compelled by fate, duty, or necessity rather than choice.

Channerin’ worm:

Channering: chattering, gnawing, rasping, often with the sense of teeth clicking or something nibbling noisily.

Worm: maggot.

(A gnawing maggot of the grave.)

Gin:

In Scots, “gin” is a conditional or temporal conjunction, meaning “if” or sometimes “when.”

Core meaning

-

gin = if

-

occasionally = when (especially in older or poetic usage)

Function

It introduces a condition or contingency, just as if does in standard English.

Examples:

-

Gin ye see him, tell him this

→ If you see him, tell him this -

Gin the wind blaws cauld

→ If / when the wind blows cold

Tone and register

-

Common in older Scots, ballads, and poetry

-

Sounds archaic or literary today, but was once everyday speech

-

Carries no special emotional weight by itself; it’s grammatically functional

“Gin” in Scots simply means “if” (sometimes “when”), marking a condition—frequently used in ballads and traditional verse.

Sair:

In Scots, “sair” means “sore”, but with broader emotional and physical force than the modern English word usually carries.

Core meanings

-

sair = sore, painful

-

physically painful

-

emotionally grievous

-

Connotations in Scots usage

Depending on context, sair can imply:

-

Deep pain or suffering

-

Hardship or severity

-

Intense grief

-

Exhaustion or distress

It often strengthens the sense beyond mere discomfort.

In ballads and poetry

In traditional Scots verse, sair commonly intensifies:

-

Grief (sair mourning)

-

Labour (sair wark)

-

Loss (sair heart)

It signals serious, heartfelt suffering, not something trivial.

Bottom line

“Sair” in Scots means sore or painful, especially in a strong or grievous sense, often applied as much to emotional pain as to physical pain.